Review of International Offset Experience

By Thomas Mathew

2013

Offsets are in essence compensations that buyers obtain from sellers for the purchase of goods and/or services. Such compensatory arrangements could form part of both defence and civil contracts. They are used for both the development of specific sectors (eg: Greece) for defence as also for the strengthening of the socio-economic sector (eg: Saudi Arabia), and generating local employment etc.

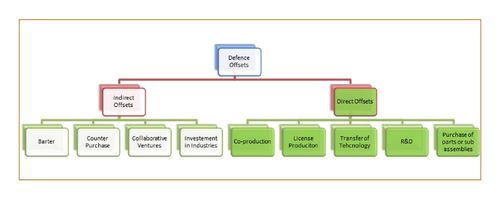

Offset transactions can be direct or indirect. Direct offsets are arrangements directly connected with the item being contracted. Though there may be different strategies for their implementation, they are characterised by this nexus. In contrast, indirect offsets are unrelated to the item being procured. A seller purchasing from the buyer nation/entity, agricultural produce for a contract for the sale of tanks, would be an instance of this form of offsets.

Offsets can also be mandatory in which case they form an integral part of the contract itself. In other words, the buyer would have to invariably perform an activity as a part of the contract for selling his ware. Offsets also tend to vary on account of the regional arrangements forged by nations as the concept of offsets evolved. Regional agreements such as EU whose policies influence offsets is such an instance. Another example is the agreement between Australia and New Zealand which have close cooperation through the Australian-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (ANCERTA) that also aims at the betterment of the business interests of local suppliers.

The evolution of the concept of offsets and its wider acceptance among nations has not, however, been steady. Though the history of offsets can be traced to the 1950s when coproduction arrangements were forged among NATO nations during the heydays of the Cold War, it was not until the closing decades of the 20th century that more nations began embracing this strategy. The policy gained greater acceptance as nations found large purchasing contracts in general useful to wrench from the sellers technological and capacity enhancement opportunities that would not have been possible but for these contracts. Consequently, the number of nations that presently stipulate offsets in defence contracts has sharply risen especially in the past two decades.

The growing perception of the advantages that could accrue by adopting the policy of offsets saw the rather small group of 20 offsets seeking nations swell their ranks to more than 130 since the 1980s. Ironically, their number witnessed more than six times rise despite the strong arguments of economists that offsets render contracts inefficient and distort trade. It has today virtually become accepted policy across continents and “Almost all European (and other countries) have adopted formalized offsets.”

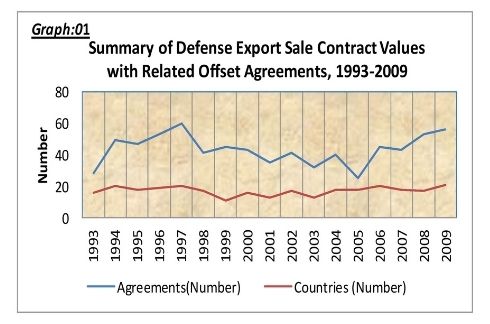

The data published by the US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security would also reveal the growing prevalence of offset provisions in defence contracts. The study of US defence contracts reveal that from 1993 to 1994, the percentage increase in the number of offset agreements was over 60. It further increased by another 30 % from 2000 to 2009 (pl. see Graph:01).

What kind of strategies are nations adopting to implement their offsets policies? Does the fact that more nations demand offsets make the inference that countries find it advantageous to pursue this policy despite strong arguments that offsets are by their very nature economically inefficient, rational? If offsets are being accepted as a beneficial strategy, then what is driving the increasing adoption of this policy?

Answers to these questions are not easy to find. By their very nature, defence contracts are shrouded in secrecy. Neither the buyer nations nor the sellers part with the details of the contracts that they conclude. Information on the experience of nations implementing offset policies is also difficult to source. Nations seldom publish or share their experience in enough detail for making an impact analyses.

India may be the best example of nations shrouding such information in the cloak of impregnable secrecy, for no ostensibly rational cause though. The three-month-long effort of the author of this paper to pry some information on India’s experience with offsets from Defence Offset Facilitation Agency (DoFA) proved utterly futile.

Despite the constraining factors, the international practices of 26 nations were studied from material in the public domain. The nations were chosen to provide contrasting experience. This study benefitted from the discussions/interviews that the author held with select implementers of the offset policy in India including some very senior functionaries in the Ministry of Defence.

This paper aims at:

• Studying the emerging international trends in defence offsets.

• Analysing the experience of select countries in the implementation of offsets with a view to understanding their preferences.

• Assessing the offset policy of India.

• Making policy recommendations for India in the light of the international trends in offsets and experience of other nations.

Modern Trends in Offsets

Overveiw

Offsets are implemented variously by nations. “Nations tailor

their offset policies to meet their specific circumstances and as such they differ in scope, complexity and implementation.” They adopt strategies calibrated to achieve their perceived domestic priorities including the strengthening of the indigenous military-industrial complex. The level of the industrial development of nations also has a bearing on the goals sought to be achieved through offset policies.

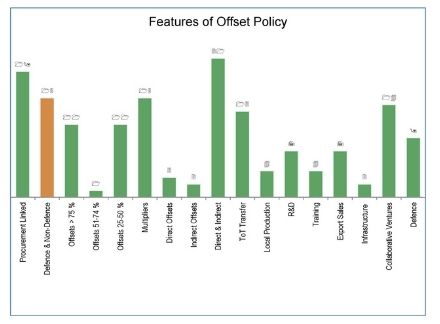

Nations not only use different strategies to implement the policy but also aim at achieving different goals by using offsets (pl. see graph: 02). For instance, out of the offset policies of 26 nations that were analysed, it is seen that 21 nations follow a mix of both direct and indirect offsets. Similarly, an equal number of countries have an offset requirement of above 75 % and in the range of 25-50 %. Similarly, 13 nations accord high priority for making Transfer of Technology (ToT) the second most preferred goal to be achieved through offsets.

Increasing Demand for Offsets

Nations are prescribing higher offset requirements. The reality is that the “magnitude of individual offset demands has increased.” Of the 26 countries, eleven countries each have requirements of offset between 25-50 % and above 75% of the contract value. Only one country has offset requirements in the range of 51-74%.

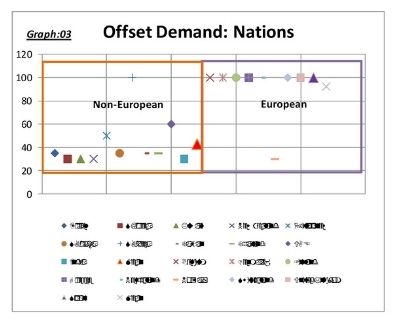

It is observed from the analysis that European nations prescribe higher offsets than those from other nations. This is borne out from the list of nations that prescribe above 75 % offsets. In this list, all except two (Canada and South Africa) are European countries. Even among these nine nations of Europe, five of them have a minimum offset requirement of 100 %. Prominent among them are Belgium, Denmark, Netherlands and UK. The remaining three aim at 100 % or more and one has a range of 80-120 %. Germany and Spain aim at 100 %. Finland in particular has provision for a minimum of 100 % plus marketing consulting. Greece which has stipulated offsets between 80-120 % falls within the former category. Norway is the only nation from the assessed 26 that has an offset requirement that makes it an outlier in Europe.

In comparison to the European nations and Canada, the countries of other regions in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, except South Africa, prescribe low levels of offsets. These nations prescribe offsets between 25-50 %.

European nations have been more successful in translating their higher offsets to greater advantage also on account of their superior technological base. Not only do they have the distinction of demanding, they also receive more offsets than those of other regions. From 1993-2004, European nations as a whole obtained offsets valued at 99.1 % of their defence imports in comparison to 46.6 % for other nations. The demand for offsets in European nations has been so pervasive that they obtained 100 % or upwards thereof in 72.9 per cent of the contracts that they had signed.

The analysis of the offset policies of 26 nations from Europe and other regions that were studied support this conclusion while revealing the following: (pl. see graph 03)

• The mean offset demand in European countries is 92.22 which is more than double that of 42.73 which is the value for non-European countries.

• Of the nations in Europe, only Norway has an offset requirement that is almost similar to the nations of other regions.

• Among non-European countries, only South Africa, Philippines and UAE, stipulate higher offsets than the mean demanded by European nations.

• The variability in offset demand in Europe is marginally higher (23.33 vs. 21.26) than that of non-Europe. The variability of offset demanded by European countries is mainly due to Norway which stands out as an outlier stipulating a requirement of only 30% offset demand. Excluding Norway, the mean would have increased to 100% and the variability would have become 0.

• The variability in percentage offset demand in Non-European countries is mainly due to South Africa which stands out as an outlier with 100% offset demands. Excluding South Africa, the mean would have reduced to 37.

Direct and Indirect Offsets

Direct offsets can take the form of co-production, ToT, Training, sourcing of parts/subassemblies/equipment/softwares to be used in the production of items contracted for procurement.

Indirect offsets generally include ToT, imports and barter, counter purchase. The chart below depicts the common kinds of direct and indirect offsets.

The offset policies of the 26 nations reveal another dimension of the offset policy: the vast majority of them use both defence and civilian contracts to generate offsets. 15 of them use both defence and civilian contracts to generate offsets for the dual purpose of strengthening both these sectors.

In contrast only 10 countries have as a norm prescribed offset requirements exclusively for defence contracts. India and UK are prominent in this category. Of these 10 countries, only three countries (India, Greece and Egypt) have prescribed only direct offsets. All the remaining 16 countries have a mixture of direct offsets both for civilian and defence procurement. Even among them the focus of Saudi Arabia and Netherlands were initially on direct offsets. From the above, it is seen that only 38% of the nations prescribe offsets exclusively for defence and only around 11 % of the countries resort to direct offsets to augment their domestic defence industry.

Direct Offsets

Direct offsets in defence are preferred by nations that seek an assured channel of augmenting their indigenous defence production capability. Through this route they seek to gain access to technology and augment their scientific and productive capabilities which would have otherwise been difficult to achieve, or would not have been feasible if it not were for the defence contracts. But in actuality, the success of direct offsets is hinged on several factors. They range from close political ties to the seller nation, indigenous military-industrial complex in the purchasing nation and the extent of its capability to absorb the technology or produce the items that may be sub-contracted to them as offsets. This would also require, as a corollary, a scientific pool of high calibre and technical capability.

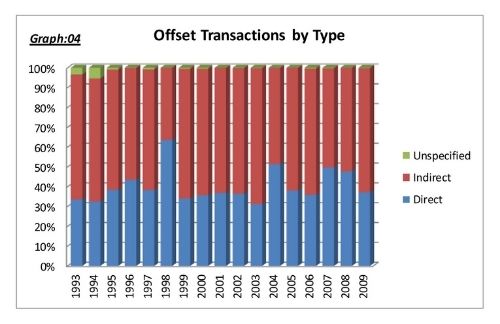

Form the available data in the public domain, it is observed that the direct offsets as a percentage of the total value of the offset contracts concluded by the US have fluctuated in the range of 38.3 % to 43. 52%. For the 5 years from 1995-99 the percentage of direct offsets of proportion of the total offsets was around 43.52 %. It then declined to nearly 38.3 % for the next five years to increase to 41.71 % for the period from 2005-09.

Indirect Offsets

An overwhelming majority of 21 nations have a mixture of direct and indirect offsets. The international experience points out that it is uncommon for nations to take recourse exclusively to direct or indirect offsets. As mentioned above, only three countries depend exclusively on direct offsets while only Thailand and the Philippines depend exclusively on indirect offsets.

The data published by the US which has been the largest exporter since 1990, reveals that during the 17 year period (1993-2009) there has been higher preference for indirect offsets. Indirect offsets registered an average of 59.05% of the value of offset contracts during the above period and have through the years moved in the narrow band of 50-68.63 % touching 36.43 % only in one year (2001). However, the three five- year- averages of the above period fall within the band of 56-62% revealing that nations have a preference for indirect offsets. The socio-economic sectors in the Middle East nations have specifically benefitted from the use of indirect offsets.

Multipliers

Multipliers are factors applied to the actual values of offset obligations to determine the credit that a buying nation is willing to assign for transactions in view of the importance it may be attaching to the fulfilment of particular obligations. These are used to direct the benefits of offsets to targeted sectors that are underdeveloped and/or non-existent in the buyer nations. Multipliers are, therefore, used to fill important gaps in the capability of the buyer nations by enhancing the values of transactions to the extent of the use of multipliers. For instance, Netherlands uses multipliers for technology transfer and applies a factor upto 10 for R&D activities.

Conversely, when a factor of less than one is used to value transactions, it implies the lower importance that a purchasing nation attaches to such transactions. Such factors are used to discourage transactions in offsets and resorted to when the particular offset obligations do not result in any desirable capability building in the purchasing nation.

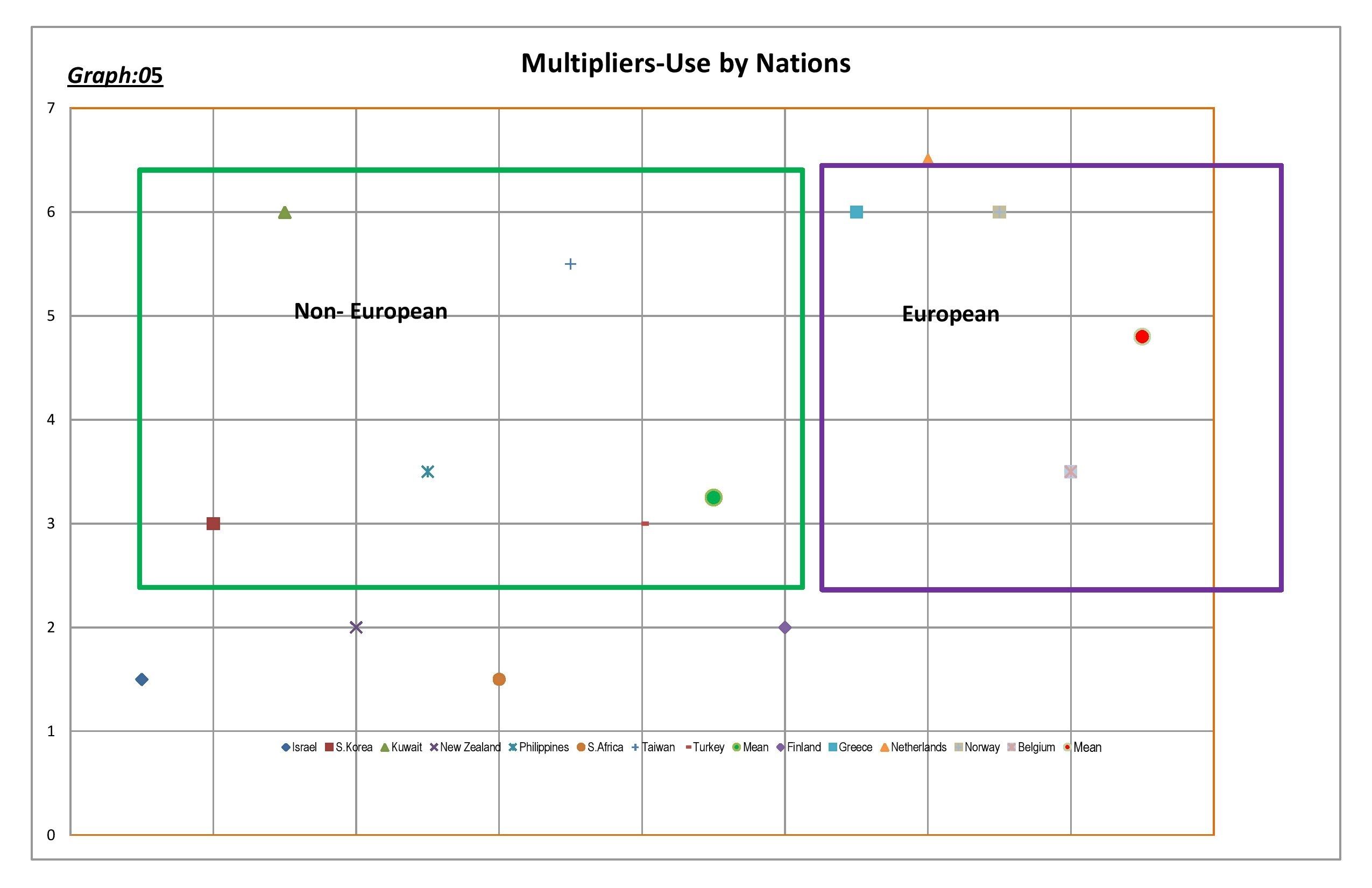

Many nations today use multipliers. Of the 26 nations assessed, 15 use different multiplier factors. They range from 1-2 (Israel) to 12 (Greece) . Graph:05 reveals the divergent levels of the use of multipliers. It also reveals that the European nations have higher multiplier factors than the non-European nations.

Even among European nations, different multiplier factors are used. The mean multiplier factor for European countries is 4.8 and is higher than that of Non-European countries for which the mean is 3.25. The variability of multiplier factor in European nations is marginally higher than that of non-European countries (1.97 Vs.1.7 respectively)

The Indian Experience

Just as the offset policy in Europe can be traced to the co-production agreements in the 1950s, India too had arrangements for the licensed production of Soviet aircraft in the 1960s. But it was only in 2005 that India unveiled its offset policy and incorporated it in its Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP). The policy underwent modifications in DPP versions of 2006, 2008 and 2011. It has therefore around six years since the offsets policy was introduced and opinions are varied on how successful India has been in implementing its offsets policy. The overwhelming view is, however, that India has not recorded significant success in translating the offsets policy to develop its military industrial complex in any appreciable manner.

In addition, the system of monitoring is so poor that it has been reported that tents and domestic air conditioners have been permitted for the discharge of offsets under the nomenclature of “Troop Comfort Equipment.” It has also been reported that Symantec Anti-Virus CDs were labeled in India and exported and offset value claimed for them in total disregard of the causality principle that is critical for determining the genuiness of offset transactions.

DPPs and Offset Provisions

The DPP 2005 laid the foundation for India’s offset policy. For the first time, all acquisitions under the “buy” and “buy and make” category having a value of above Rs.300 Crores (US $ 66.66 m) were required to have an offset of 30% of the value of equipment being contracted. The offset obligation could be discharged by exporting Indian defence products and / or services. Investments in the indigenous defence infrastructure were also made eligible. But the SCAP Categorisation Committee (SACPCC) could decide on whether the offset provisions should be included as a part of the acquisition.

As the policy lacked clarity and any formal structure for the implementation of the policy, it failed to take off. In view of this, the policy was modified in the 2006 DPP. It made offsets compulsory, providing for the establishment of Joint Ventures (JVs) and established the DoFA.

Offset Policy in DPP-2008

The changes made in DPP 2006 also yielded virtually no result and the policy was further modified in 2008. The modifications included the listings of items eligible for the discharge of offset obligation, introduction of offset credit banking and exempting the fast track acquisitions from the offset obligations.

The policy was further modified in 2011 to include civil aerospace, internal security and training within the scope of eligible items for the discharge of offset obligation. Therefore, to this extent, India has departed from its strict policy of “direct” or “quasi-direct” offset provision in its 2006 and 2008 policies.

Review of Indian Offset Policy

From all accounts, India’s experience with offsets has not been encouraging. Neither is the policy geared towards delivering optimum results, nor is the system of implementation robust. There has to be an almost complete overhaul of the offsets architecture as is obtaining in India.

The need for undertaking this exercise cannot be over-emphasised. Defence offsets come at a cost and empirical studies have shown that the premium in the cost is transferred to the buyer and it is still unclear as to who benefits from such transactions. In a study of a defence procurement in Belgium, it was concluded that the cost of the acquisition was hiked up between 20-30 % of the actual value on account of offset provisions.

Like other nations that implement offset policy, India too would have to bear the risk of its policy not being able to derive optimum results and suffer economically inefficient transactions if the strategies adopted to implement is not carefully calibrated. The risk of economic inefficiency of contracts involving offsets becomes greater when offsets are mandatory. This happens as sellers factor in the cost of the equipment, the inefficiencies, lack of military-industrial base, technical manpower etc. in the buyer nation.

Nearly 70% of India’s defence wares are imported. With its economy growing at 8-9 % per annum its defence outlays would see significant growth. Given the current level of growth in defence expenditure it is estimated that India’s imports in the decade beginning 2011 could be US$ 100billion. Though it is difficult to reach a clear estimate on the offset value that could be involved in the imports, it is estimated that it could be in the region of US$30 billion. The implementation of this value of offset is both an opportunity and a challenge at the same time.

In view of the foregoing, what are the changes that India should make in its offsets polices? The following recommendations are based on the international best practices, its moderate defence industry, state of its industry and steadily increasing defence budget

Enhancing Offset Limit

India is one of the few nations that prescribe only 30 % offsets. The only other country in the study that prescribes the same threshold that India has is Norway. But there cannot be any comparison between the defence imports of both the countries. While India in 2010, imported defence equipment of the value of USD 3337 million that of Norway was USD 205 million.

Of the 26 nations surveyed, the mean offset demand prescribed by the 8 European countries is 91.25 %. In case, Norway is excluded for the reasons stated above, the mean would be a perfect 100%. Given the large size of India’s imports, there is no reason why its offset requirements should be less than 100 %.

The entire 100 % cannot, however, be in the defence sector. India at present would neither have the capacity to implement offset transactions of this aggregation if the offset limit is raised to 100% nor would sellers be in a position to discharge them as beneficially as would if the policy is also extended to the civilian sector.

It is recommended that India prescribe 100 % offsets with 40 % for defence and the balance 60 % or more in strategic sectors like power, telecommunication, mining and transport and important social sectors like education and health. Extending offset to social sectors would bring attractive dividends. For instance, investment of technology and finance in taking education to villages through satellite links could have enormous long-term positive spinoff for Indian’s economic growth.

India could, therefore, reserve 40 % for direct & Quasi-direct and 60 % indirect offsets. India has sufficient industrial capacity to absorb offsets in these sectors including TOT. After all, defence budgets come at a social cost to the nation and it would only be prudent for leveraging the influence large defence contracts give to buyer nation for the benefit of these sectors. It is not unusual for countries to use indirect offsets. India could take a lesson from Saudi Arabia that used the Peace Shield contract for barter, forging equal partnership with local businessmen and used the indirect offset provision for setting up local production of pharmaceutical, petroleum and food processing industries.

Use of Multipliers

India does not use multipliers. Though it is understood that this issue was debated extensively in the MoD, the majority view was not in favour of adopting this strategy. It should also be admitted that of the 8 implementers of the Indian offset policy who were sent questionnaires only two have supported the use of multipliers. All those who have opposed it state that the time is not ripe for it but do not give any reasons to support their contention. On the other hand, the two who have supported the use of multipliers have credible experience in implementing offsets and one represented one of the largest companies in the aerospace industry.

International experience too, does not support the exclusion of offsets for a country like India. Of the 26 countries studies, 14 use multipliers and their list includes technologically advanced economies like Israel, South Korea, Netherlands and Norway. South Korea has particularly used multipliers to obtain technology. If these nations can resort to the strategy of multipliers to achieve development in targeted areas, there is little reason why India should not. In comparison to all the above nations, India could likely benefit from sharp focusing its development in critical areas as it has a large defence industry of middling sophistication.

For a nation that is even slated to be the largest economy in PPP terms by the middle of this century defence of critical importance not only for sustaining the present level of growth but also for protecting its national interests. The country’s defence industry could get a boost by strengthening directional moves using offsets. For the reasons that have been stated in the preceding paragraph, it would be desirable to introduce the system of multipliers. Multipliers could also be used for encouraging tie-ups with (Small and Medium Enterprises) SMEs that operate in the defence sector.

Multipliers could be used to fill critical gaps in existing technology in India. There are several cases of defence equipment that could be produced in India if some critical gaps are filled. For instance the multipliers could be used to obtain the technology for the engines of India’s MBT tank which have been bedevilled because of the lack of a powerful enough engine. Another area that could benefit from the use of multipliers is in Indian warship production capability in which we have made great progress but lack the domestic capability in the fire control systems. Another example cited by an interviewee is the use of multipliers for the “Towed Array Sonars.” For instance, multipliers could be used to obtain ToT for these systems.

FDI in Defence Sector

India could do well to increase the share of FDI in defence. Foreign manufacturers would not set up industries in India unless they have the comfort of controlling and managing the entities that they establish. They would need the assurance of adequate returns on their investment and security of the technology that they transfer and it can only come from atleast a majority shareholding. The present limit of 26 % FDI in defence is a disincentive for any meaningful level of investment by foreign companies.

Further, limiting the shareholding to 26 % holding would also cast additional burden on Indian companies intending to establish partnerships as they would have to raise the remaining 74 %. As the defence industries are highly capital intensive, it would require huge outlays by Indian companies.

Unless the foreign entities have enough incentive, they would not establish units in India. The reality is that companies do not establish entities abroad that can create competition for the parent company. Therefore, foreign firms should be given sufficient control over the entities that they create. In this way, they would be assured of control and continuing profit in a country whose defence budget could steadily grow. Such a policy could be used in conjunction with offset banking that is allowed in India. It is strongly argued that offset credit trading should be allowed in specific areas to ensure that companies would be encouraged to produce within the country either for their supply chain or for India’s defence requirement. In order to achieve the latter, they could be mandated to continuously modernize to get orders.

There is no ostensible reason why FDI cannot even be raised to 100 % in special cases where for instance a critical defence industry is established. Without giving foreign companies full control of the important entities they create, there is little chance of them establishing defence industries involving critical technology in India. If it is feared that it would be a threat to India’s nascent domestic industry, it could also be stipulated that production of items being already produced in the country would have to be undertaken in participation with the existing domestic industry. And as for the commonplace argument that we could lose our technology, it is stated that we cannot lose what we do not have.

Involvement of domestic Industry in Defence Planning

Indian defence industry should be involved in the planning, approval and monitoring of offsets. If defence offsets are to be directed, then it is necessary for offsets to fill the critical gaps. The nature of gaps that are existing would be in the knowledge of the industry more than any other. They should also be made privy to India’ s fifteen-year Long Term Integrated Perspective Plan (LTIPP) that flows and the five-year Services Capital Acquisition Plan (SCAP) which in turn flows into the two year roll on plan for Capital Acquisitions.

There is no major country in the world that keeps their acquisition plans from their defence industry and there is no reason why India should be adopting a different policy.

Introduce offset credit trading

DPP 2008 allows for offset banking with a permissible timeframe of two-and-a-half years. In practice, however, they may get along with the lead-time available for Request For Proposals (RFPs), a total of 5 years or more depending on the completion schedule of the proposal. The implementers of the offsets who were sent questionnaires suggested strongly that the offset banking should be made between 7-10 years. This is something that should be considered positively.

There is growing opinion that offset transactions should not end with the end of the project. It is also argued that allowing offset commitments to stretch across several projects rather than mandating its compulsory extinguishment at the end of the project would reap greater dividends. One of the offset implementers to whom the questionnaire was sent clearly stated that “offset partners have tried to create capabilities that they could encash in future.” This clearly points to the fact that opportunities should be created for foreign entities to derive benefits on the long-term basis for them to be fully invested in India which would be to the benefit of the nation. To fully harness the potential of FDI in India it would be necessary to look at giving foreign entities majority holding which could be dovetailed with offset trading.

Trading of offsets could bring in several benefits. It could encourage long-term investment in defence as companies making such investment would be assured of not only returns from the expanding markets in India, but also be confident of obtaining credits for the offset by trading them to winners of future contracts. Restrictions could be placed on the number of years credits could be held unless new technology is inducted.

Directing Offsets

The list of eligible items is at Annexure -VI of DPP 2011 is generic in nature. It would be desirable to list the technology that the Indian industry lacks and include them in the items that would be made eligible for the discharge of the offsets listing key technologies that should be inducted. On the other hand, listing out items that may be eligible for the discharge of offsets without them being a part of a well-conceived strategy to build capability in critical areas, may not be the correct strategy. Listing out items would give the sellers the option to even manufacture through a JV a small part of any of the listed items and discharge obligation without adding in any way to the strengthening of the capabilities of India’s defence system.

The reorganized DoFA could be given the authority to fine tune the exact nature of technology for inclusion in the RFP. By precisely directing offsets, nations have been able to achieve production of important defence items. On the other hand, vaguely defined national interests also do not result in substantial benefits and what may accrue through offsets may not be appreciable. When directed and foreign entities are assured of future orders for equipment on the condition that they are technologically upgraded at regular intervals it would help fill gaps in Indian technology.

Increase Threshold Value

The threshold value or the minimum contract value for requiring offset transactions varies across countries. A study of 33 countries revealed that the threshold ranges from a low of US$ million 1 (Austria)-59 (Switzerland) excluding India. The mean of these countries is 13.38 million US$.

In comparison to the international mean, India’s threshold is US$ 66.66 million making it the highest among the 33 countries. This would mean that India would stand to lose out on several opportunities for generating offsets. It is opined that India would do well to adopt both direct and indirect offsets, lower the threshold/trigger for offsets. Such a move could benefit many industries export their products and also help obtain technology to fill gaps in the civilian sector. It is recommended that the threshold be reduced to US$ 10 million.

Strengthening DoFA

Even with the current threshold and low rate of offset requirements, it is estimated that in the next 10 years (2011-20), the value of offsets to be discharged would be US$30 billion. This would require the establishment of a strong agency that draws its expertise not only from the Government sector, but also from outside.

The present system is woefully inadequate to deal with the elaborate planning, evaluation and monitoring of offsets. Just as the defence acquisition wing was established in MoD, it would be necessary to establish a wing exclusively to deal with offsets. If the threshold is reduced to US $ 1 million and the minimum requirement of offset is enhanced to 100 %, with 40 % for direct and 60 % for indirect offsets, then it is necessary to have such an organisation.

The manpower for this organisation should be drawn from the Government including civilian ministries, services, public sector undertakings, both defence and civil, industry associations and from the open market. As the efficacy of the offset policy would depend on detailed planning, implementation and monitoring, it is important for it to be headed by an Additional Secretary Officer designated as DG, Offsets.

Conclusion

Most countries today demand offsets for the purchase of defence wares. Nations demand direct offsets to primarily augment their indigenous military capability while indirect offsets are used to develop other sectors including the socio-economic sector and create domestic employment opportunities.

The majority of nations use both direct and indirect offsets and do not depend exclusively on either though the preference is for the latter. Multipliers are also being increasingly used to direct development in areas of priority.

There is virtually no goal that is not sought to be achieved using these compensatory arrangements. Some have preference for ToT, while others have for R&D related offsets. There is no one shoe that fits all. Priorities are laid down by government according to the conditions prevailing in their territories.

There is also greater demand for offsets. The majority of nations have higher offset requirements. The trigger for offset also varies and India is at the highest end of the spectrum.

Despite the inherent loading of offset cost in contracts, nations obviously prefer employing them for the net benefits that accrue from them. Therefore, offsets are here to stay and would only become more sophisticated in the decades to come.

India has, however, been a late entrant in the field. Only six years have passed since it adopted this policy and all indications are that India has still not been able to put in place an imaginative policy and a cogent, effective and robust organisation to implement it.

Consequently, India’s policies are in variance with the international practice in several parameters. It has a very high offset trigger, very low offset requirement, is predominantly direct in nature, does not allow ToT etc. and the organisation that has been assigned the responsibility of overseeing the offset policy is neither properly staffed, nor does it any strong monitoring system. Not surprisingly, all the implementers who were interviewed have unanimously stated, the foreign sellers obliged to discharge offsets are having a field day getting away with “soft” offsets.

If offsets have to bring in net benefit, then there has to be strong incentive for the seller to seriously be involved in the implementation of offset transactions. Atleast 51 % FDI has to be permitted in the defence sector. It need not be through the automatic route, but granted on a case-to-case basis. In special circumstances, if the seller is willing to set up production centres for equipment that India does not have the capacity to produce, then even 100% FDI should be allowed.

Multipliers should be used to direct capacity building in identified areas. Offset banking should be allowed to extend beyond the life of projects and sellers setting up production centres in India should be given assured orders over longer periods at rates using the price discovery mechanism.

Most important would be the creation of an independent DoFA headed by an officer of the level of Additional/Special Secretary to government of India and staffed by technical experts, financial managers, project management specialists etc drawn from the government, services, private industry etc. Personnel in DoFA should be recruited for their capability and integrity.

The present policy therefore needs to be revisited and DoFA replaced by an efficient body.

- Susan Willett and Ian Anthony, Countertrade and Offsets Policies and Practices in the Arms Trade, Copenhagen Peace Research Institute at: http://www.ciaonet.org/wps/wis01/ (Accessed 20 June 2011)

- US Report to Congress -2007 Offsets in Defense Trade Seventh Study at: http://www.bis.doc.gov/defenseindustrialbaseprograms/osies/offsets/7thoffsetsreport.htm (Accessed on 20 June 2011)

- Data for the graph has been compiled from US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Offsets in Defence Trade: Fifteenth Study, December 2010 at http://www.bis.doc.gov/news/2011/15th_offsets_defense_trade_report.pdf. (Accessed on 20 June 2011)

- The details of the offset provisions were obtained from the site: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Offsets in Defence Trade: Sixth Study, at www.bis.doc.gov/defenseindustrialbaseprograms/osies/offsets/01rept.doc. (Accessed on 20 June 2011). But wherever it was possible to verify the details from the official sites of countries, the same has been done and the information was modified accordingly. For instance, in the US site, UK is shown as a nation that uses multiplier. But in EU site at: http://www.eda.europa.eu/offsets/ UK is shown as a nation that does not use multipliers. Therefore the information from the EU sites was used to update the details of offset regulations of countries (Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Netherlands and Switzerland were updated).

- Ron Kane , “National Governments and their Defence Industrial Bases: A Comparative Assessment of Selected Countries”, Canadian Association of Defence and Securities Industries, October 2009 at https://www.defenceandsecurity.ca/UserFiles/File/IE/Annex%20G%20%20International%20Researh.pdf (Accessed on 17 June 2011)

- R. Lee Hessler,“The Impact of Offsets on Defense Related Exports”, Defence Institute of Security Assistance Management at http://www.disam.dsca.mil/pubs/Vol%2011-1/Hessler.pdf (Accessed on 18 June 2011)

- Germany has officially no offset policy. Germany reserves the right to introduce “work share equals cost share” in cooperative programmes. As German government requests no indirect offset the relative part of direct offset equals 100 % in this case. Pl. see: http://www.eda.europa.eu/offsets/

- The data is not confined to the European nations in the 26 countries. US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Offsets in Defense Trade: Tenth Study, December 2005 at: http://www.bis.doc.gov/defenseindustrialbaseprograms/osies/offsets/offsetxfinalreport.pdf (Accessed 20 June 2011).

- US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Offsets in Defence Trade: Sixth Study, no. 4. Canada was, however, excluded while plotting the graph to maintain the geographical proximity to the extent possible. Turkey was excluded because of offset demand changing under various situations, Australia and Egypt not specifying any offset requirements, Germany not having any declared offset requirement and that of Sweden marked as NA.

- In India, the Civil Aviation Ministry has introduced offsets for the purchase of planes. Offsets are also being considered in other Ministries. See: http://www.rediff.com/money/2008/dec/06national-offset-policy-soon-to-aid-local-industries.htm

- Calculated from data available at: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Offsets in Defense Trade, Fifteenth Study, December 2010 at http://www.bis.doc.gov/news/2011/15th_offsets_defense_trade_report.pdf

- M. Asif Khan, “Market Trends and Analysis of Defense Offsets”, The DISAM Journal, 32(1), July 2010 at: http://www.disam.dsca.mil/pubs/Vol%2032_1/Journal%20%2032-1%20Web%20Jul%201.pdf (Accessed on 18 June 2011).

- Ron Kane, no.5.

- Greece has a very complex system of applying multipliers and the maximum permissible is the factor of 12. For the calculation of mean, where ranges have been mandated, the midpoint of the range has been taken. For instance, Israel has a multiplier in the range of 1-2 and, therefore, 1.5 midpoint has been taken for plotting the graph.

- Though 15 nations use multipliers, only those of 13 nations have been plotted to make the graph as Saudi Arabia leaves multipliers to the discretion of the authorities while UAE has not disclosed the factor they use. UK was excluded for the reasons stated at footnote no. 4.

- From the written replies to the questionnaire sent by the author.

- From the interview with a middle level officer of MoD.

- Converted at the rate of 1 US $ = Rs. 45

- Peter Hall and Stefan Markowski, On the Normality and Abnormality of Offsets Obligations, Defence and Peace Economics, 1994, Vol.5, p-175. Quoted in Lloyd J. Dumas, Do offsets mitigate or magnify the military burden? in Jurgen Brauer and J. Paul Dunne, Arms Trade and Economic, development: Theory, Policy, and Cases in Arms Trade Offsets (Routledge London and New York, 2004).

- Wally Struys quoted in Stephen Martin quoted in Lloyd J. Dumas, Do offsets mitigate or magnify the military burden? in Jurgen Brauer and J. Paul Dunne Arms Trade and Economic, development: Theory, Policy, and Cases in Arms Trade Offsets (Routledge London and New York, 2004), p-21

- Stefan Markowski and Peter Hall, The Defence Offsets Policy in Australia, quoted in Stephen Martin (eds) The Economics of Offsets: Defence Procurement and Countertrade, Harwood Academic Publishers, The Netherlands, 1996, p-50.

- Economic Times, October 4, 2010 at: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2010-10-04/news/27620854_1_defence-sector-defence-procurement-policy-defence-ministry ((Accessed on 18 June 2011)

- Pl. see http://www.sipri.org/contents/armstrad/output_types_TIV.html

- Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

- United States General Accounting Office, Military Exports, Offset Demands Continue to Grow, Washington, D.C., April 12, 1996 at: http://dodreports.com/pdf/ada309999.pdf (Accessed on 25 June 2011)

- Various assessments point out that India would attain this status in 2050. For instance see: http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-02-23/india-business/28626519_1_largest-economy-citi-indian-economy

- For elaborate reasoning on how multipliers could benefit India, pl. see: Thomas Mathew, “Essential Elements of India's Defence Offset Policy - A Critique”, Journal of Defence Studies, 3(1)2009, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi.

- Jurgen Brauer, Economics aspects of arms trade offset in Jurgen Brauer and J. Paul Dunne Arms Trade and Economic, development: Theory, Policy, and Cases in Arms Trade Offsets (Routledge: London and New York, 2004).

- In the questionnaire sent to Mr. P Soudnarajan, Director, Planning and Marketing, HAL, he aired the same opinion stating that there may not be much change in the disinclination of foreign companies to invest in India “even if the cap is increased to 49 % since even the OEM will not have total management control”.

- Ron Matthews Defense offsets: policy versus pragmatism in Jurgen Brauer and J. Paul Dunne Arms Trade and Economic, development: Theory, Policy, and Cases in Arms Trade Offsets (Routledge :London and New York, 2004).

- Udis quoted in Ron Matthews Defense offsets: policy versus pragmatism in Jurgen Brauer and J. Paul Dunne Arms Trade and Economic development: Theory, Policy, and Cases in Arms Trade Offsets (Routledge: London and New York, 2004).

- The name of the official and the name the company he represents are being withheld on the request of the interviewee.

- Jurgen Brauer, Economics aspects of arms trade offsets in Jurgen Brauer and J. Paul Dunne Arms Trade and Economic, development: Theory, Policy, and Cases in Arms Trade Offsets (Routledge: London and New York, 2004).

- For detailed justification, how directing offsets would benefit a country like India, pl. see: Thomas Mathew, “Essential Elements of India's Defence Offset Policy - A Critique”, Journal of Defence Studies, 3(1)2009, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi.

- Figures have been rounded to avoid decimal points. In addition, Slovenia which has a threshold of 0.57 million USD has been ignored to determine the country with the lowest threshold.

- Figures to calculate threshold have been taken from sites: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Offsets in Defence Trade: Sixth Study, at www.bis.doc.gov/defenseindustrialbaseprograms/osies/offsets/01rept.doc., http://www.eda.europa.eu/offsets/ and http://www.defence.gov.au/deu/docs/Offsets_Database.xls Where countries were not listed in the first site, the second site was relied upon and likewise when the first two sites lacked clarity the third site was relied upon. Where ever clarity was lacking the same progression was followed. All currencies were converted to US$ using the conversion rate as on 11th July 2011.

(Accessed June 20, 2011)